Part One: presenting the five zone model

Are you looking to take your endurance training to the next level? The three-zone and five-zone endurance training models are two popular frameworks used by athletes and coaches to optimize their training efforts. These models offer different approaches to structuring workouts, and each has its own unique benefits and drawbacks. In this three part series, we will dive into the similarities and differences between the two models to help you decide which one is best suited for your training goals.

Whether you’re a beginner training for your first competition or an experienced athlete aiming to improve even further, we’ve got you covered. So, let’s explore the three-zone and five-zone endurance training models and find out which one is right for you!

What is the five zone training model?

The five-zone training model is a framework used in endurance training to help athletes structure their workouts and optimize their training efforts. This model is based on the idea that different exercise intensities produce different physiological responses in the body, and that by varying the intensity of workouts, athletes can target specific training adaptations. E.g. high volume training at a lower intensity to improve aerobic capacity and fatmax.

How are the five zones defined?

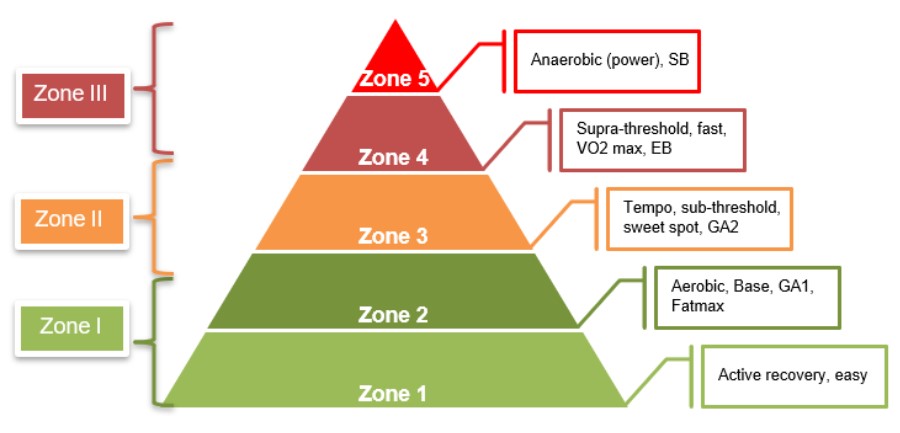

The five-zone training model was popularized by Dr. Andrew Coggan and Hunter Allen, and is based on the concept of Functional Threshold Power (FTP), which is the highest power output an athlete can maintain for one hour without fatigue. The five zones are defined as follows:

Zone 1: Active Recovery (Endurance):

This is the lowest intensity zone, used for recovery and restorative workouts. The effort level is very low and can be maintained for long periods. The purpose is to improve blood flow and recovery.

Zone 2: Aerobic (Endurance):

This zone focuses on building the aerobic base and improving endurance. It is a moderate intensity zone, where an athlete can maintain a conversation but feels somewhat challenged. Workouts in this zone typically last between 2-5 hours.

Zone 3: Tempo (Sup Threshold):

This zone is characterized by a moderate to high intensity level, where an athlete can no longer maintain a conversation. Intensity zones such as sweet spot training and up to the point of the maximal lactate steady state (MLSS) fall into this zone. Workouts in this zone typically last between 30-60 minutes.

Zone 4: Supra threshold (VO2 Max):

This zone is characterized by high intensity, and is used to improve VO2 max, or the maximum amount of oxygen an athlete can use during exercise. Lactate accumulates faster than it can be utilized by the body. Workouts in this zone typically last between 4-20 minutes.

Zone 5: Anaerobic (Power):

This zone is characterized by maximum effort, where an athlete can only sustain the intensity for seconds to a few minutes at a time. Workouts in this zone are used to improve power and speed, and typically last between 30 seconds to 2 minutes.

In summary, the five-zone training model provides a structured approach to endurance training by varying the intensity and duration of workouts to target specific physiological adaptations. This model can help athletes improve their performance and reach their training goals. In the next section we will present to you the three zone model which is also applied in the norwegian training method.

Bibliography on the five-zone training model in endurance training:

Coggan, A. R., & Allen, H. R. (2010). Training and racing with a power meter (2nd ed.). VeloPress.

Jeukendrup, A. E., & Gleeson, M. (Eds.). (2019). Sports nutrition: From lab to kitchen. Routledge.

Laursen, P. B., & Jenkins, D. G. (2002). The scientific basis for high-intensity interval training: optimising training programmes and maximising performance in highly trained endurance athletes. Sports Medicine, 32(1), 53-73.

Seiler, S., & Kjerland, G. Ø. (2006). Quantifying training intensity distribution in elite endurance athletes: is there evidence for an “optimal” distribution?. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine &

Science in Sports, 16(1), 49-56.

Steinacker, J. M., Lormes, W., Lehmann, M., Altenburg, D., & Hundsalz, H. (1998). Training of junior rowers before world championships. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 30(7), 1153-1161.